The case for Rosie

Dublin People 21 Jun 2013

THERE are currently 16 bridges over the River Liffey in Dublin. Thirteen are named after men and not one after a real women (the fictional Anna Livia Bridge in Chapelizod is the closest we’ve got).

Former trade unionist and Irish Citizen Army member Rosie Hackett is one of the favourites in the quest to find a name for Dublin’s latest Liffey bridge.

From a list of over 70 she’s made it into the final ten, but who was Rosie Hackett and why should we back her?

Well here’s the story of who she was and what she did.

On April 2 1911, the census returns for No 3 Abbey Street show six members of the Gray family and two members of the Hackett family, Christina and Rosanna.

Their father had died 10 years previously and the mother had remarried Patrick Gray in 1903. The census records Rosanna as being 17-years-old. She can read and write and works as a packer in the Jacob’s paper store. Her stepfather Patrick is a caretaker in a warehouse.

On August 22, 1911 3,000 women, led by young Rosie, withdrew their labour at Jacob’s factory in pursuit of a pay claim. Jim Larkin said the conditions for the biscuit makers were

“sending them from this earth 20 years before their time

?.

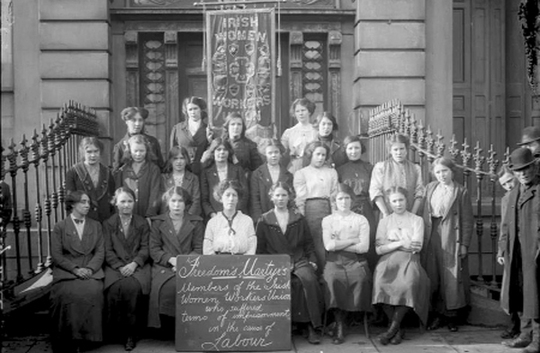

Rosie joined the Irish Women Workers’ Union (IWWU) when it was founded a month later by Delia Larkin.

In August 1913, when the tram workers went on strike, Rosie and her fellow workers from Jacob’s again mobilised in support of the pickets and gathered in O’Connell Street on August 31 for a rally against employers.

She was in the crowd that was baton charged by the police, resulting in terrible injuries to workers that made the day infamous as ‘Bloody Sunday’.

On the following Saturday, three Jacob’s workers were sacked for refusing to remove their ITGWU badges and Rosie was one of the organisers of the supporting strike which began immediately afterwards.

The employers retaliated by locking out all the workers and Rosie began a period of tireless work, bringing together the members of the IWWU to provide physical and moral support for the strikers throughout the city.

As a result of her efforts during the lockout, Rosie was not re-employed by Jacobs, and instead, took up a full-time post as clerk to the IWWU.

In 1916 in the days leading to the Easter Rising, Rosie was one of the small group who endeavoured to print the 1916 Proclamation on a faulty printing press.

She took the first copy off the press, still damp, and placed it into the hands of James Connolly.

She was a member of the Irish Citizen Army and served with Constance Markievicz and Michael Mallin when they occupied the Royal College of Surgeons in the Easter Rebellion and was sent to Kilmainham Gaol.

On her release she re-founded the Irish Women Workers’ Union with Louie Bennett and Helen Chenevix and for years served as clerk for the organisation, which, at its peak, organised some 70,000 women.

Later she took charge of the ITGWU’s newspaper shop on Eden Quay (where the new bridge is sited). Rosie died on July 4, 1976 at St Vincent’s Hospital when her heart failed.

Her address was 115 Brian Road, Marino. She was 82 years of age and had never married. She is buried with her mother and stepfather in grave marked XG 52 at St Paul’s, Glasnevin Cemetery.

So I call on Dubliners to support naming the new bridge the Rosie Hackett Bridge. Why? Because 2013 is the 100th anniversary of the Great Lockout when anonymous workers like Rosie stood for the rights they deserved. Because all too often the role of Irish women is forgotten in our history books. And because Hackett Bridge just sounds right.