History remembering the Eureka Rebellion

Dublin People 10 Oct 2015

IN December 1854, gold diggers at the Eureka Gold Mines in Ballarat, Australia, rose in armed rebellion against the Colonial Authorities and the British Army.

Although the rebellion was savagely supressed, the diggers won widespread support and their actions are credited with the introduction of universal suffrage for white males.

As a result, the Eureka Rebellion is considered one of the key events in the birth of Australian democracy.

From an Irish point of view the rebellion is interesting. Many of the rebels were Irish and its leading architect was Peter Lalor, a brother of the famous Irish revolutionary James Fintan Lalor.

Tension at the mines had been growing for some time. The colonial administration was particularly corrupt and had little interest in the rights of workers. From the miners’ point of view, the administration was only interested in lining their own pockets.

This was confirmed in 1851, when the authorities introduced ‘mining licences’, as a legal device for taxing the gold miners.

The diggers rejected the licences and protests began. The administration began to use intimidation to enforce their rule, by instructing the police and British Army to check licences twice a week.

The situation came to a head in October 1854, when a pro-British gang in the town, led by the local publican James Bentley, murdered a Scottish digger named James Scobie.

Due to their standing in Ballarat, the magistrate refused to convict and the gang were acquitted.

The miners decided to seek justice themselves. On October 17, a large crowd of diggers protested at Bentley’s Hotel and Bar, which were burned to the ground.

The arrest of three miners in connection with the fire, sparked a mass meeting that decided to establish a ‘Diggers’ Rights Society’.

On November 11, following the arrest of seven more miners including Irishmen, the ‘Ballarat Reform League’ was established to peacefully campaign for diggers’ rights.

With peaceful tactics soon failing, the miners decided it was time for open resistance.

A new militant leadership, led by Peter Lalor, was elected. Lalor immediately ordered the establishment of a military organisation.

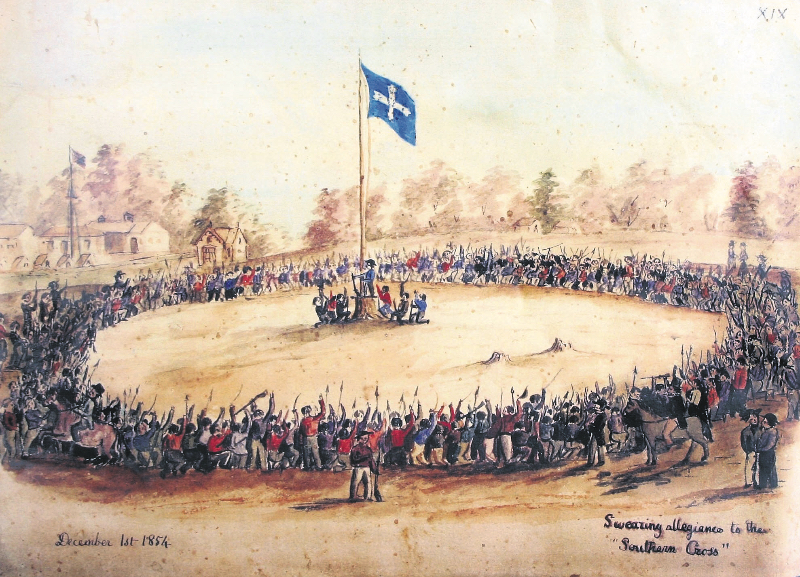

The search was now on for arms. In a defiant move the diggers also unveiled their own flag, ‘The Southern Cross’, which has since become the Australian Flag for Independence.

The miners took an oath which read: “We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other and fight to defend our rights and liberties”.

Lalor now ordered the building of a stockade at Bakery Hill as a rallying point for the diggers. This was not a defensive or military structure, but the authorities viewed it as an act of war.

Following the mass burning of licences by the diggers the authorities decided to act.

At 3am on December 3, a large force of police and British soldiers approached the stockade and attacked. The diggers defended themselves, but were soon overrun by the better trained professional forces.

The police and soldiers then set about massacring the miners. Rebel women showed tremendous courage by throwing themselves on injured miners in an attempt to save them.

Despite this bravery, some 27 diggers were killed and more are believed to have died from their wounds.

The rebellion was over, but its aftermath would have widespread repercussions for British rule in Australia. Peter Lalor survived the rebellion and became regarded as a hero. He later stated: “we were compelled to take the field in our own defence, we were unable (through want of arms, ammunition and a little organisation) to inflict on the real authors of the outbreak the punishment they so richly deserved.”