A group of proud Dublin dockers is asking the city to remember one of its bravest sons, a man whose quiet courage saved lives and whose story, they believe, deserves a permanent place on the streets where he worked.

The Dublin Dock Workers Preservation Society (Facebook Dublin Dockers) are looking to get William Deans honoured for his bravery.

Working with the family of William Deans, they have produced a song, Unsung Hero, in the hope that it gets some publicity and that a plaque is erected in his honour.

For many people across the Northside, the docks are more than a workplace.

They are a way of life, a community, and a history built on hard work, early mornings, and men who did whatever was needed to get through the day. William Deans was one of those men.

He was a ‘casual’ docker from Foley Street, doing the kind of job that asked everything of a person and often gave very little back.

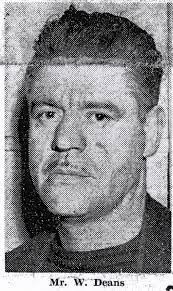

William Deans

But what makes William Deans stand out, even among a community known for toughness, is the fact that he is still the only Irish citizen to have received two Bravery Awards from the State.

His acts of bravery started in 1939.

He was crossing the Ballybough Bridge (now the Luke Kelly Bridge) when he noticed a young boy drowning in the Tolka.

There was no time to hesitate, no time to call for help, no time to weigh up the danger.

He immediately jumped over the wall and rescued him.

It is one moment, one split second of decision, but it tells you everything about the man.

A young life in trouble, and William Deans moved towards it without hesitation.

He became a docker at a very young age, following in the footsteps of his father.

The work was tough and the hardship was real, but there were chances to earn a bit extra if you had skill and could avoid the most punishing jobs.

On the 12th November 1947 he was picked to drive a winch on a coal boat, the SS Amaso Delano.

Some companies, to save some money, instead of using quayside cranes would use ships cranes, winches positioned at each hatch.

If a docker was skilled he could get the job of driving the winch, thereby earning an extra few ‘bob’ and avoiding the extreme hardship of shovelling coal.

But even in a job that was already dangerous, nobody could have expected what would happen next.

On the 12th November 1947, having been picked to drive a winch, William Deans was standing on the deck when he began to smell gas.

The gas was coming from the second hatch.

The Captain, Engineer and Bosun went into the hatch to investigate.

It is suspected that the previous cargo was grain and that it was not cleaned properly before it was loaded to the rim with coal.

Then the unthinkable happened.

The three crew collapsed with the poisonous fumes, and all crew and dockers were told to ‘abandon ship’ to the safety of Sir John Rogerson’s Quay.

Everyone obeyed except William Deans. He stayed and risked his life.

In the middle of panic, in the middle of danger, in the middle of men being ordered to run to safety, he did the opposite. He stayed.

Putting a handkerchief around his mouth, he climbed down the ladder into the hatch and with some difficulty carried each one of them up the ladder and carried them to safety where they were rushed to hospital.

Two other crewmen on the deck had reached over to look into the hatch to see what was happening and they collapsed.

William said he went to the first one and slapped them in the face in the hope of reviving him but no luck, so again he carried them ashore.

The three seriously injured were rushed by awaiting ambulances to hospital and after a period in hospital they made a full recovery.

Behind the medals and certificates, there is always a family living with the aftermath, always a house waiting for news, always children trying to understand what their father did and why.

Newspaper reports on William’s brave act of heroism

His son Christopher, as a young child, remembered that when the Captain and the fellow seamen got out of hospital it was around Christmas time and they turned up in his house with a basket of presents for the family (and a little bit of cash) to thank William.

They were the best Christmas presents that Christopher had ever gotten.

It is a small detail, but it carries a lot of truth. It speaks to the gratitude of the men whose lives were saved, and the impact William’s bravery had far beyond the docks themselves.

It also speaks to the kind of household it must have been, where something like that was remembered for a lifetime.

In 1947 the Irish Government introduced the Deeds of Bravery Act, and William was the first citizen to be awarded a bronze medal and an official certificate.

But William’s story did not end there.

In one of life’s strange coincidences, in 1957 at roughly the same spot a French sailor, suspected of being drunk, fell off the gangway of a ship into the Liffey.

William, without hesitation, jumped in and had some difficulty saving him. William was again awarded a Bravery Certificate, and he is the only person in Ireland to have received two Bravery Awards from the Irish State.

Now, decades later, the Dublin Dock Workers Preservation Society want that courage to be properly recognised.

They want William Deans remembered not just in family stories and dockside memories, but in a way that everyone can see, a plaque in his honour, a marker that says this city notices its own.

Dublin Dock Workers Preservation Society also want to thank Dublin Port and The Little Museum for their support.

Readers can listen to Unsung Hero by clicking on this link